Research area: Environmental Governance and Policy

Clearing the air through the revised WHO guidelines

International Environmental Law in the Courts of India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan

Summary

This chapter, published in The Oxford Handbook of International Environmental Law, focuses on international environmental law (IEL) in the courts of India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. Review of the case law reveals that Indian courts have led the adoption of the IEL principles in this region, with occasional references to IEL by Bangladeshi and Pakistani courts. This appears to follow the trend of non environmental cases, where also the Bangladeshi and Pakistani judiciary is more reluctant than the Indian courts to turn to international law. Although courts in the three countries have engaged with IEL, it has mostly been at a superficial level. Their reliance on IEL is not always accompanied by strong judicial reasoning, making it difficult to determine their content and scope, and even their relevance in particular scenarios. Given development imperatives in these countries, courts are often faced with the ‘economy/development versus environment’ question. In such situations, the courts rely on IEL in an instrumental fashion in support of the final outcome of the case, rather than engaging with the substantive content of the IEL principles.

Read moreDaily nonaccidental mortality associated with short-term PM2.5 exposures in Delhi, India

Abstract

Background:

Ambient particulate matter of aerodynamic diameter less than 2.5 microns PM2.5) levels in Delhi routinely exceed World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines and Indian National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for acceptable levels of daily exposure. Only a handful of studies have examined the short-term mortality effects of PM in India, with none from Delhi examining the contribution of PM2.5.

Objectives:

We aimed to analyze the association between short-term PM2.5 exposures and daily nonaccidental mortality in Delhi, India.

Methods:

Using generalized additive Poisson regression models, we examined the association between daily PM2.5 exposures and nonaccidental mortality between June 2010 and December 2016. Daily exposures to PM2.5 were estimated using an ensemble averaging technique developed by our research group, and mortality data were obtained from the Municipal Corporations of Delhi and the New Delhi Municipal Council.

Results:

Median exposures to PM2.5 were 91.1 µg/m3 (interquartile range = 68.9, 126.2), with minimum and maximum exposures of 21.4 µg/m3 and 276.7 µg/m3, respectively. Total nonaccidental deaths recorded in Delhi during the study period were 700,512. Each 25 µg/m3 increment in exposure was associated with a 0.8% (95% confidence intervals [CI] = 0.3, 1.3%) increase in daily nonaccidental mortality in the study population and a 1.5% (95% CI = 0.8, 2.2%) increase in mortality among those with 60 years of age or over. The exposure-response relationship was nonlinear in nature, with relative risk rising rapidly before tapering off above 125 µg/m3. Meeting WHO guidelines for acceptable levels of exposure over the study period would have likely averted 17,526 (95% CI = 6,837, 25,589) premature deaths, with older and male populations disproportionately affected.

Discussion:

This study provides robust evidence of the impact of short-term exposure to PM2.5 on nonaccidental mortality with important considerations for various stakeholders including policymakers and physicians. Most importantly, we find that reducing exposures significantly below current levels would substantially decrease the mortality burden associated with PM2.5.

Climate Litigation in India

Summary

India is one of the countries most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. It is also one of the highest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters in the world, although its per capita GHG emissions are very low. An active participant in international climate negotiations, India’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) is considered 2 °C compatible, and its current policy framework is likely to support two of the three targets set out in its NDC.

While the success of the policy framework will be determined by various social, environmental, economic and political factors, it will also depend on the ability of individuals to hold public and private actors accountable for their actions (and inactions), which aggravate the causes and impacts of climate change.

A review of the legal and regulatory landscape in India reveals that the main environment and energy related laws, policies and regulatory processes offer several hooks to bring climate claims to courts. While there have been cases where courts have referred to climate concerns, there is yet to be a judicial decision on the justiciability of climate claims, or one that directs measures specifically for mitigation or adaptation. The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of India and the High Courts as well as that of the National Green Tribunal is quite broad, and they could potentially decide various types of climate claims. However, one should not be overly optimistic as Indian courts often refrain from interfering in government decisions and policies on infrastructure development and Indian courts are notorious for their overflowing dockets and massive judicial delays.

What Can COVID-19 Teach Our Government About Communicating Air Quality?

EIA 2020: Two Steps Back…

Introduction

The Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MoEFCC) published the draft Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification 2020 in the Official Gazette on 11 April 2020. If brought into force, it will replace the existing EIA Notification 2006. It has met with widespread public opposition. According to some reports, the Environment Ministry has received 17 lakh representations in response, and politicians across party lines have strongly opposed the draft. In this essay, Shibani Ghosh provides a brief overview of the environment clearance process under the EIA notification, and discusses four principal reasons why the 2020 draft is misconceived and should be withdrawn. She then contextualizes these reasons within the broader regulatory landscape of the 2006 notification. As India awaits far-reaching regulatory reforms, Ghosh proposes four ways in which the existing regulatory framework can be strengthened to achieve significant environmental and social gains.

Read moreLeveraging Existing Cohorts to Study Health Effects of Air Pollution on Cardiometabolic Disorders: India Global Environmental and Occupational Health Hub

Abstract

Air pollution is a growing public health concern in developing countries and poses a huge epidemiological burden. Despite the growing awareness of ill effects of air pollution, the evidence linking air pollution and health effects is sparse. This requires environmental exposure scientist and public health researchers to work more cohesively to generate evidence on health impacts of air pollution in developing countries for policy advocacy. In the Global Environmental and Occupational Health (GEOHealth) Program, we aim to build exposure assessment model to estimate ambient air pollution exposure at a very fine resolution which can be linked with health outcomes leveraging well-phenotyped cohorts which have information on geolocation of households of study participants. We aim to address how air pollution interacts with meteorological and weather parameters and other aspects of the urban environment, occupational classification, and socioeconomic status, to affect cardiometabolic risk factors and disease outcomes. This will help us generate evidence for cardiovascular health impacts of ambient air pollution in India needed for necessary policy advocacy. The other exploratory aims are to explore mediatory role of the epigenetic mechanisms (DNA methylation) and vitamin D exposure in determining the association between air pollution exposure and cardiovascular health outcomes. Other components of the GEOHealth program include building capacity and strengthening the skills of public health researchers in India through variety of training programs and international collaborations. This will help generate research capacity to address environmental and occupational health research questions in India. The expertise that we bring together in GEOHealth hub are public health, clinical epidemiology, environmental exposure science, statistical modeling, and policy advocacy.

Read moreDraft EIA notification dilutes environmental protections, is in denial of ecological crises

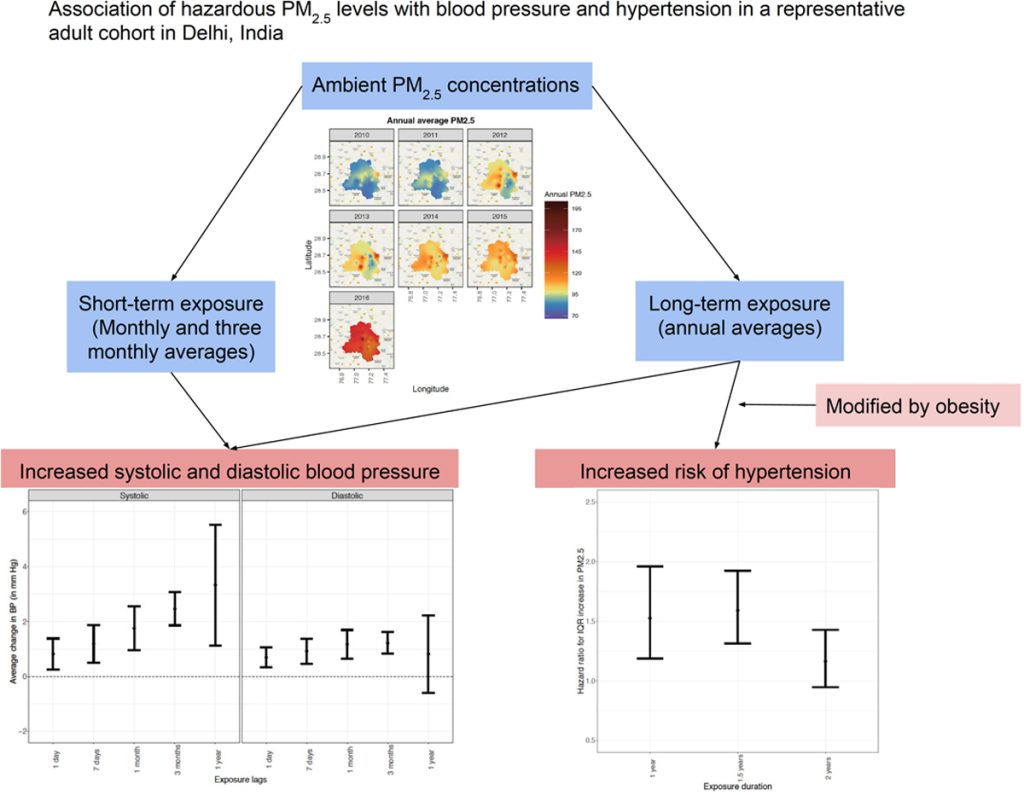

Exposure to Particulate Matter Is Associated With Elevated Blood Pressure and Incident Hypertension in Urban India

Abstract

Ambient air pollution, specifically particulate matter of diameter <2.5 μm, is reportedly associated with cardiovascular disease risk. However, evidence linking particulate matter of diameter <2.5 μm and blood pressure (BP) is largely from cross-sectional studies and from settings with lower concentrations of particulate matter of diameter <2.5 μm, with exposures not accounting for myriad time-varying and other factors such as built environment. This study aimed to study the association between long- and short-term ambient particulate matter of diameter <2.5 μm exposure from a hybrid spatiotemporal model at 1-km×1-km spatial resolution with longitudinally measured systolic and diastolic BP and incident hypertension in 5342 participants from urban Delhi, India, within an ongoing representative urban adult cohort study. Median annual and monthly exposure at baseline was 92.1 μg/m3 (interquartile range, 87.6–95.7) and 82.4 μg/m3 (interquartile range, 68.4–107.0), respectively. We observed higher average systolic BP (1.77 mm Hg [95% CI, 0.97–2.56] and 3.33 mm Hg [95% CI, 1.12–5.52]) per interquartile range differences in monthly and annual exposures, respectively, after adjusting for covariates. Additionally, interquartile range differences in long-term exposures of 1, 1.5, and 2 years increased the risk of incident hypertension by 1.53× (95% CI, 1.19–1.96), 1.59× (95% CI, 1.31–1.92), and 1.16× (95% CI, 0.95–1.43), respectively. Observed effects were larger in individuals with higher waist-hip ratios. Our data strongly support a temporal association between high levels of ambient air pollution, higher systolic BP, and incident hypertension. Given that high BP is an important risk factor of cardiovascular disease, reducing ambient air pollution is likely to have meaningful clinical and public health benefits.

Read more