India’s hydrogen demand is expected to double, reaching approximately 12 million metric tonnes per annum (MMTPA) by 2030, driven primarily by the expansion of the fertiliser, refinery, and petrochemical sectors. India currently meets most of its hydrogen demand from natural gas via steam methane reforming. As the country pursues its targets for energy independence by 2047 and Net-Zero emissions by 2070, green hydrogen has arguably emerged as a key component of its energy transition calculus.

India launched the National Green Hydrogen Mission (NGHM) in January 2023 with an outlay of INR 19,744 crores and a target to achieve 5 MMTPA green hydrogen production capacity by 2030. Produced by renewable energy (RE) powered electrolysers, green hydrogen can potentially decarbonise ‘hard-to-abate’ sectors. Building on strong private-sector interest and additional support from state governments, the country now aims to secure 10% of global green hydrogen production capacity, which is projected to surpass 100 MMTPA by 2030.

Can green hydrogen truly become the game-changer it is hailed to be? Our blog analyses India’s pursuit of green hydrogen, examines the opportunities, challenges, and risks in its current approach.

Pursuit of Green Hydrogen

The hype around green hydrogen has fuelled ambitious targets and high expectations. Meeting the NGHM target would require installing 60-100 GW of electrolyser capacity. It is expected to leverage over INR 8 lakh crore investments and create 6 lakh green jobs. Besides the financial incentives, the Government of India (GoI) has streamlined permits and waived transmission charges for RE procurement. Several states have announced or are working on policies to support green hydrogen and its derivatives.

Four promising narratives shape India’s green hydrogen ambition:

– Decarbonise hard-to-abate sectors: Green hydrogen and its derivatives are positioned as key solutions for decarbonising hard-to-abate sectors where direct electrification is impractical or inefficient, such as energy-intensive industries (like steel and cement), long-haul road transport, shipping, and aviation. India supports hydrogen technology demonstration projects in these sectors.

– Generate employment: Green hydrogen production and export are expected to become a significant driver of job creation. The NGHM is expected to generate over 6,00,000 jobs by 2030, an aspiration shared by the states. Andhra Pradesh aims to create 12,000 jobs per MMTPA of green hydrogen production, while Uttar Pradesh’s policy envisions generating 1.2 lakh direct and indirect jobs. Gujarat is projected to create 1.8 lakh jobs owing to opportunities in hydrogen electrolyser manufacturing.

– A vehicle for industrialisation: While India sees green hydrogen as an opportunity to reduce its dependence on fuel imports, it also aims to become a global hub of production, use, and export of green hydrogen and its derivatives. It is looking to tap into the green hydrogen export markets in Europe and East Asia. Cheap RE, lower labour and land costs, and access to multiple ports across the long coastline are claimed to bolster India’s export capabilities. GoI has sanctioned four hydrogen valley clusters in Bhubaneswar (Odisha), Jodhpur (Rajasthan), Kochi (Kerala), and Pune (Maharashtra), and has designated three green hydrogen hubs in Paradip (Odisha), Tuticorin (Tamil Nadu), and Kandla (Gujarat).

– Address regional imbalances: The eastern and north-eastern states, currently lagging in solar and wind energy development, can capitalise on the green hydrogen transition by leveraging their rich mineral and industrial base. A TERI study claims industrial clusters offer a promising opportunity for the early development of hydrogen infrastructure. Notably, the iron and steel industries are concentrated near coal and iron ore deposits in Odisha, Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Chhattisgarh. Green hydrogen is an opportunity for these states to leap forward in their energy transition.

The Challenges

However, the pursuit of green hydrogen is not free from challenges. Realising the promises will require managing these challenges.

– Domestic market: The NGHM has spurred a significant supply-side response, with announced production capacities reaching nearly 2.5 times the 2030 target. However, this momentum has not translated to the demand side. The biggest hurdle right now is cost. Green hydrogen costs about $4–$5 per kg, while grey hydrogen is much cheaper at $2.3–$2.5 per kg. By 2030, financial incentives and falling solar and wind energy prices can bring the cost of green hydrogen production to around $3–$3.75 per kg. Still, it’s unlikely to match grey hydrogen anytime soon. Creating demand through strategies such as blending in high-volume sectors (refining, fertiliser, piped natural gas) or replacing grey hydrogen in niche industries (chemicals, glass, ceramics) might help.

– Export demand: Exports could help boost uptake of green hydrogen. If export opportunities are fully tapped, NGHM targets could be exceeded to 10 MMTPA. To support export, GoI is prioritising the development of port infrastructure, including storage and refuelling capabilities, and has identified strategic export hubs. Encouraging demand signals from markets willing to pay a premium for low-carbon hydrogen, like Germany, Japan, South Korea, the Netherlands, and Belgium, further reinforce this ambition. However, uncertainties surrounding the export market and evolving standards compound the problem. Energy losses across the supply chain (production, compression/liquefaction, storage, and reconversion) of hydrogen and its derivatives further raise doubts on the reliability of the export-oriented strategy.

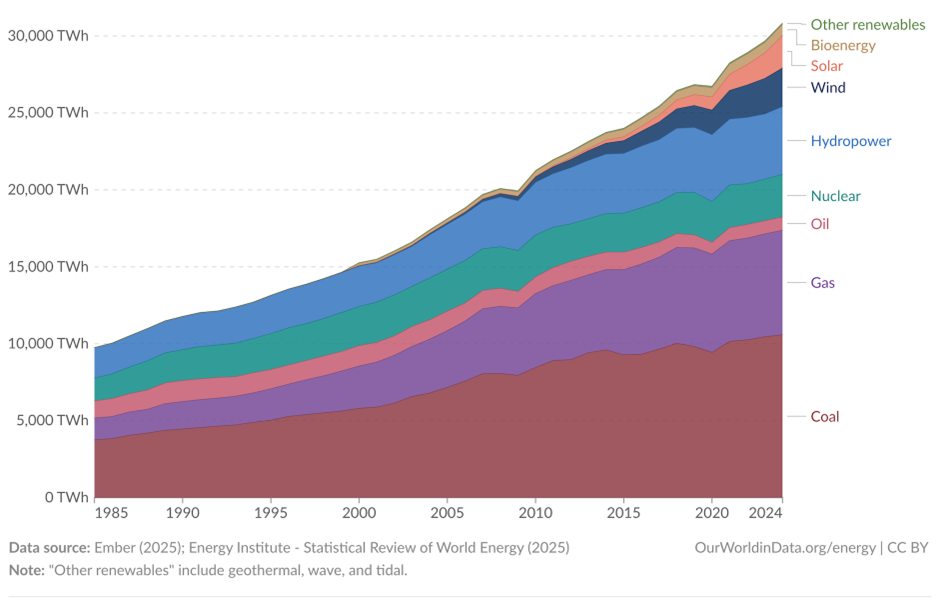

– Powering green hydrogen: The NGHM envisages an additional 125 GW of RE capacity for green hydrogen production. However, India’s 2030 target for 500 GW non-fossil electricity generation capacity does not account for this demand. Even if the target is met, a CSEP study claims, it will be insufficient to meet rising electricity demand. At the current pace of RE deployment in India, green hydrogen risks competing with other critical electricity demands, thereby spiking demand for coal-fired electricity.

Another critical consideration is India’s RE mix. Wind-Solar Hybrid electrolysers have demonstrated higher capacity utilisation compared to standalone solar or wind systems. Greater reliance on wind within the mix can further optimise utilisation and reduce levelised costs. However, India’s installed wind capacity (52 GW) is less than half of its solar capacity (130 GW), creating an imbalance that could hinder cost-effective green hydrogen production.

– Resource constraints: Low volumetric energy density poses challenges for hydrogen’s transportation, storage, and distribution infrastructure. Delays in infrastructure development, insufficient subsidies, policy uncertainties, lack of mandates, unreliable grid power, and land availability are delaying Final Investment Decisions (FID). Furthermore, India’s reliance on China for critical and rare-earth minerals needed in electrolyser manufacturing raises significant supply chain concerns.

The cost of electrolysers is expected to decline, aided by policy measures like production-linked incentives. However, low demand may defer commissioning of electrolysers. Financial professionals estimate the technology risk associated with green hydrogen, given evolving technologies such as electrolysers, fuel cells, and storage, as compared to proven technologies like solar and wind. India’s limited focus on hydrogen technology research and development (R&D) leaves it ill-equipped to adapt to rapid advancements.

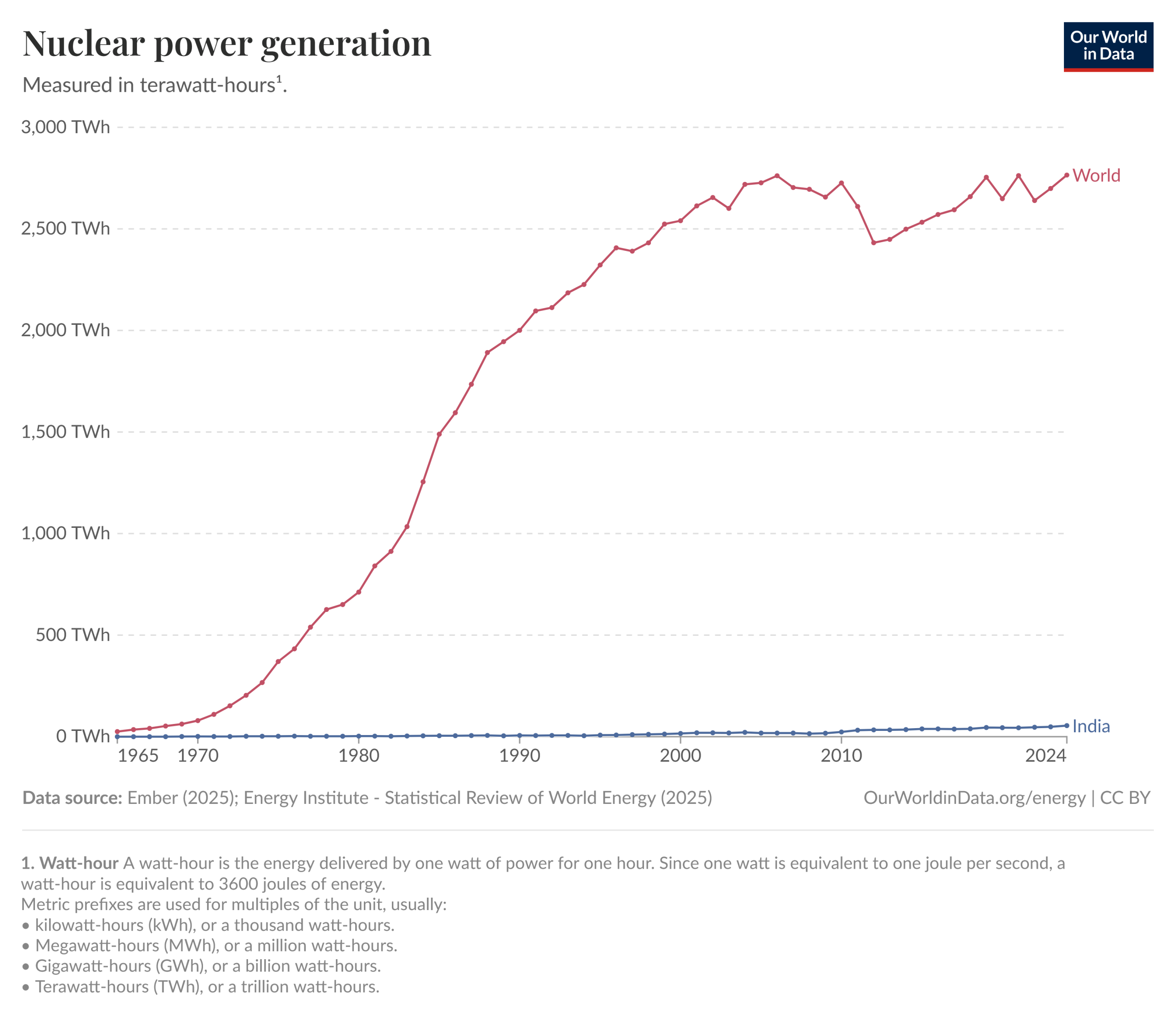

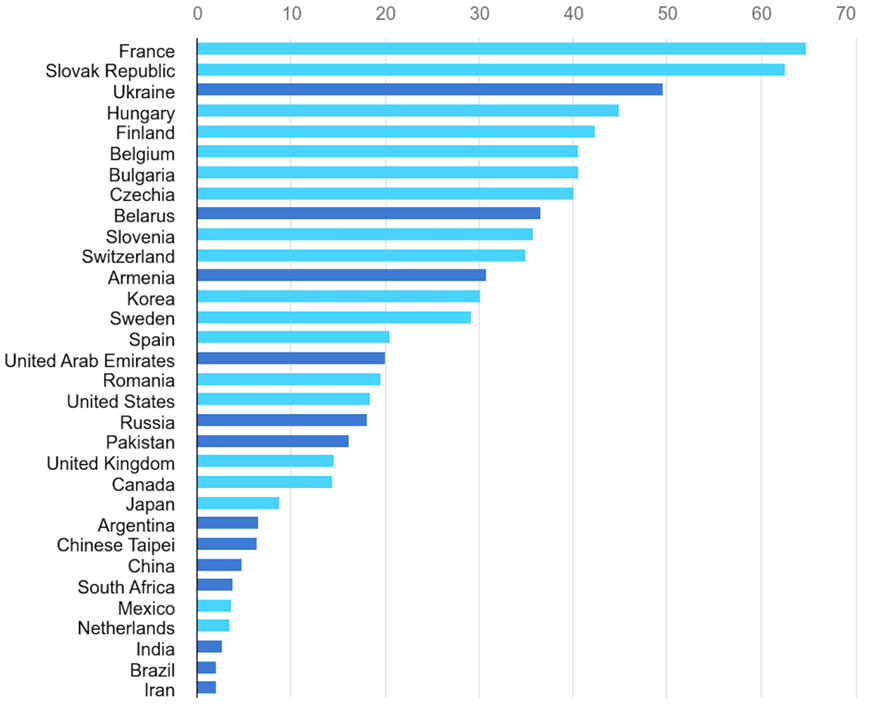

India’s hydrogen demand is projected to grow over 50 MMTPA by 2070, prompting calls to explore alternative low-carbon sources. Geological surveys suggest that India may hold 3,475 million tonnes of natural hydrogen (white hydrogen), which can potentially meet the demand until green hydrogen becomes viable. Other potential options include pink hydrogen, produced using nuclear power, and blue hydrogen, derived from natural gas with carbon capture and storage. However, these options involve unproven technologies and high costs.

Beyond its role in decarbonisation and energy security, green hydrogen presents new development paths for late-industrialising countries like India. India regards green hydrogen as a first-mover advantage to secure technological and market leadership in clean energy. However, current policies and fiscal measures are geared largely toward deployment rather than innovation. India’s modest public spending on R&D does not reflect the scale of its ambitions. For more details on the green hydrogen R&D landscape, see our blog.

The global surge in green hydrogen is criticised as a form of green extractivism, framing resource appropriation as a climate imperative. India’s current strategy, along with that of other developing nations, focuses on leveraging export opportunities, risks replicating the extractive patterns of fossil-fuel economies. Mitigating these risks calls for an approach grounded in environmental justice, redistribution, and a transformative vision.