Green hydrogen is often positioned as India’s next clean energy frontier. In 2023, the country set a goal to produce 5 million metric tons of green hydrogen annually by 2030, under the National Green Hydrogen Mission (NGHM). The mission is framed as the centrepiece of India’s vision to achieve net-zero emissions by 2070, reduce emissions and fossil fuel imports, and position itself as a global leader in green hydrogen technology1.

The NGHM recognises the importance of innovation and outlines a three-tiered framework that spans near-term, industry-linked projects, mid-term component advances, and long-horizon, high-risk research to build future technological capabilities. It has proposed a Strategic Hydrogen Innovation Partnership (SHIP) to pool public and private resources and earmarked ₹400 crore ($47 million) for research and development (R&D). However, this represents only about 2% of the total mission outlay of ₹19,744 crore ($USD 2.3 billion). Additionally, ₹1,466 crore ($172 million) has been allocated for pilot projects in sectors like steel, mobility, and shipping. Most of the funding is allocated to the Strategic Interventions for Green Hydrogen Transition (SIGHT) programme, which has demarcated ₹17,490 crore ($2.1 billion) in incentives to scale electrolyser manufacturing and green hydrogen production.

While private investment is beginning to flow into green hydrogen production and manufacturing, particularly through incentive schemes such as SIGHT, early-stage research and demonstration activities continue to be anchored in public funding and public-sector institutions in India. As of early 2025, 23 R&D projects have been awarded grants under the NGHM across areas such as hydrogen production from biomass, hydrogen applications, and non-biomass hydrogen production routes. The limited R&D allocation raises questions about whether India’s publicly funded green hydrogen R&D efforts are sized and timed to deliver the long-term technological and market leadership the NGHM envisions.

Why Hydrogen Innovation is Different

Hydrogen is a multi-system technology involving electricity, water, materials, and industrial processes. Unlike solar or battery technologies, which can advance through stand-alone improvements in modules, materials, or manufacturing, hydrogen innovation relies on the seamless interaction of production, storage, transport, and end-use. Each step in the process is deeply interconnected, and efficiency gains in one part can be lost if the rest of the chain is not aligned. For instance, a breakthrough in electrolysis means little without affordable storage or reliable industrial demand. Progress, therefore, takes longer, costs more, and relies on close coordination between researchers, engineers, and industries.

What the Public R&D Portfolio Shows

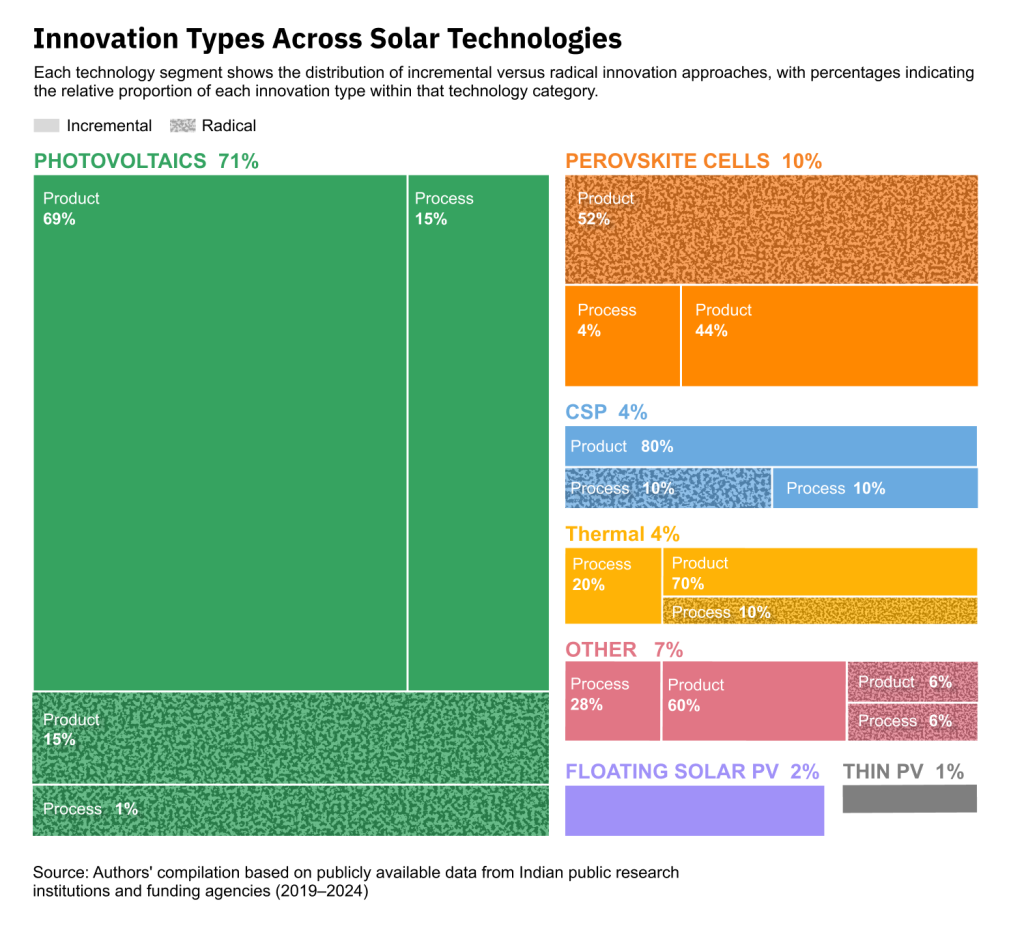

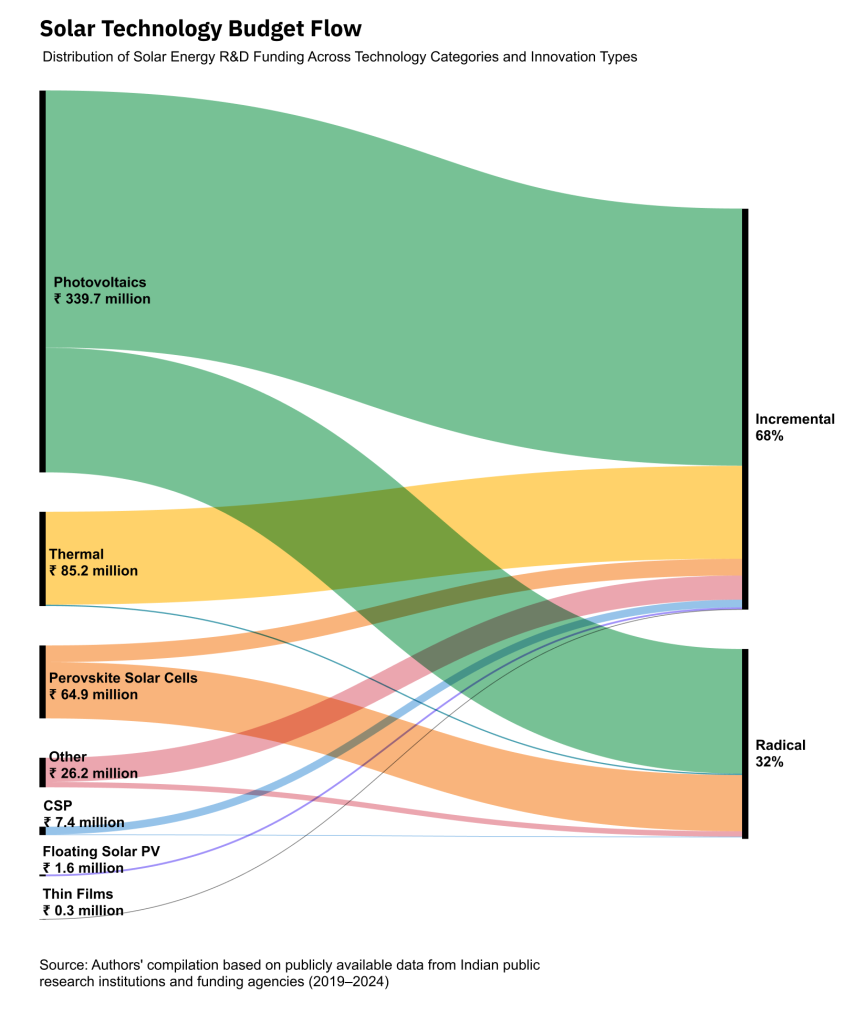

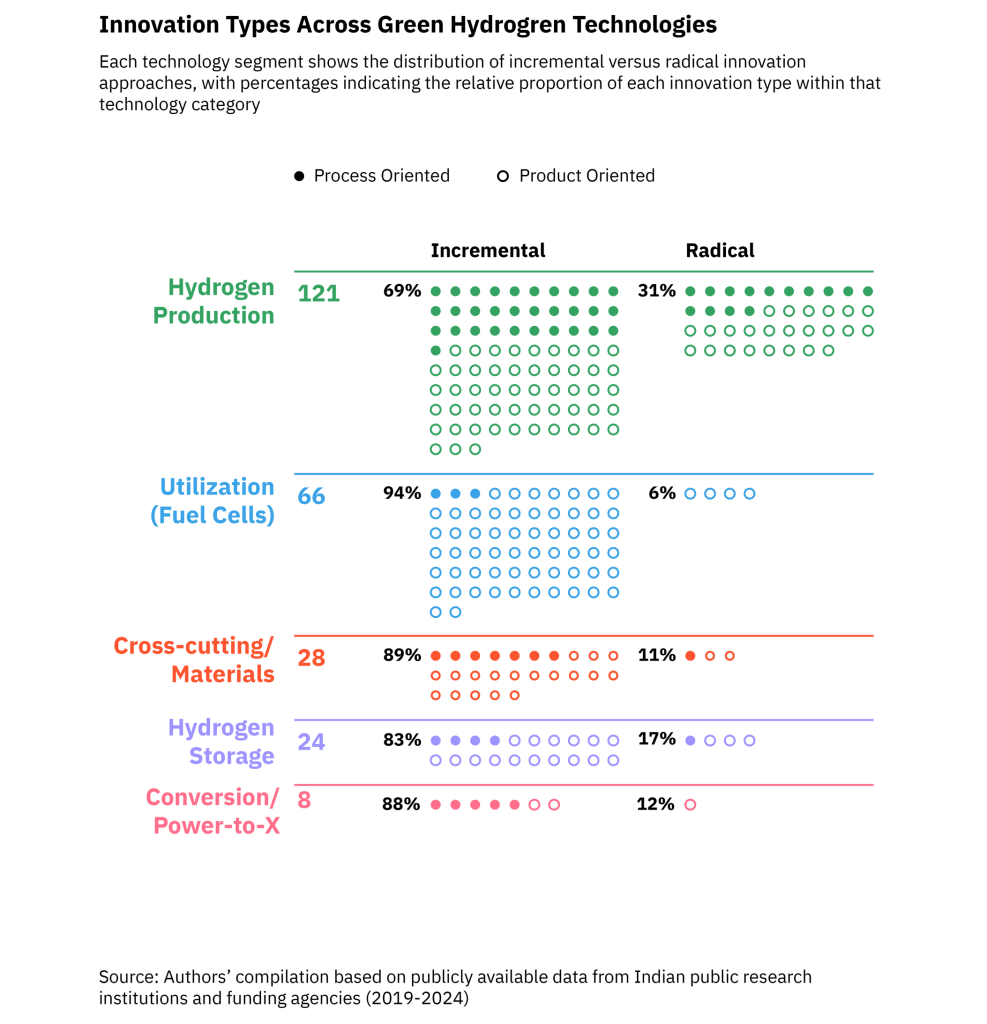

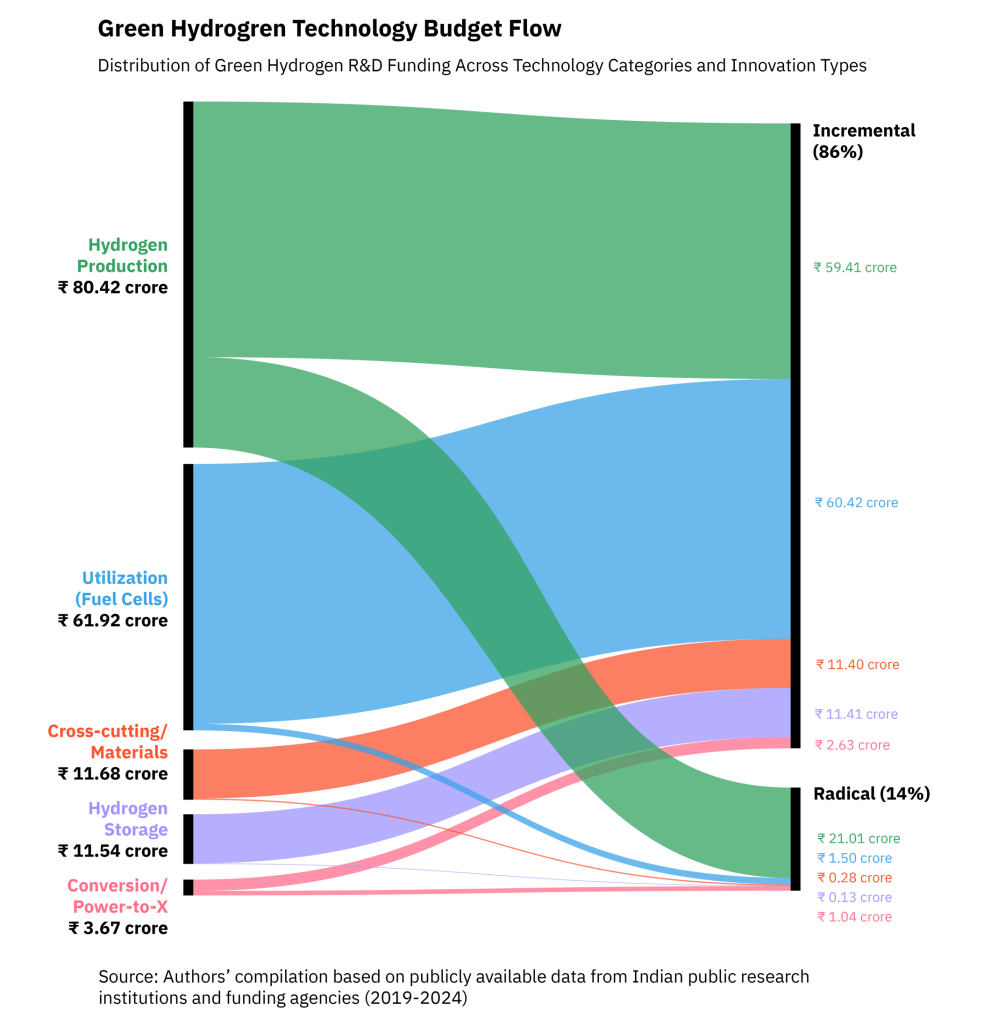

Drawing on our review of almost 250 publicly-funded hydrogen research projects between 2019-24, across Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) laboratories, national institutes, and other government-supported centres, a clear pattern emerges. Most of India’s hydrogen research activities are aimed at incremental improvements, to address crucial knowledge gaps, build domestic capabilities, and reduce production costs. This mirrors the pattern we noted in our analysis of solar R&D, where innovation has largely focused on making technologies more affordable and better adapted to Indian conditions rather than creating frontier breakthroughs. Incremental, cost-oriented innovation aligns with India’s comparative advantage – low renewable electricity costs, high solar irradiance, and a rapidly expanding transmission network – and points to an R&D portfolio oriented toward cost-competitive green hydrogen for domestic deployment and cost-sensitive export markets.

As seen in the figure above, much of the current focus lies in the development of electrolysers2 and fuel cells, the backbone of hydrogen production and conversion. Here, research is directed at membranes, catalysts, and stack optimisation across a range of chemistries, including proton exchange membrane (PEM)3, alkaline4, and solid oxide cells5. Scientists are working to reduce dependence on expensive metals such as platinum, improve membrane durability, and enhance performance under local operating conditions.

A related stream of incremental work focuses on integrating electrolysers with variable renewable power, which remains one of the most challenging aspects of hydrogen deployment globally. In India, some research institutions, such as IIT Madras and IIT Guwahati, are focused on developing solutions to manage intermittency and maintain grid stability as hydrogen production scales.

Nevertheless, the scale of funding constrains laboratory research from moving to the demonstration phase. Many projects fall within the ₹20–70 lakh ($23.5-82.3K) range, sufficient for exploratory research but not for pilot-scale demonstrations. Even the more ambitious efforts, such as the development of a 20 kW fuel cell system at the Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (IIST), are small compared with the multi-million dollar and multi-megawatt demonstration projects already underway in other countries. For example, Japan’s Green Innovation Fund allocates between JP¥ 30–220 billion (₹1,700–12,500 crore) to individual hydrogen demonstration projects, and the US Department of Energy has been funding $10–150 million (₹80–1,200 crore) demonstration-scale projects. While India’s lower labour and operational costs allow the rupee to stretch further, the order-of-magnitude difference in resources remains striking.

Alongside these incremental efforts, a smaller set of radical projects explores new directions altogether. For instance, CSIR-AMPRI has piloted a hydrogen-powered desalination system, linking clean energy with water security. IIT Delhi and IIT Mandi are developing techniques to split water using sunlight as the primary energy input, reducing reliance on external electricity during operation. IIT Jodhpur and IIT Madras are exploring hydrogen–ammonia fuel blends for industrial applications, while IIT (BHU) Varanasi is testing new reformer designs for ultra-pure hydrogen production. These projects have the potential to define future technologies, but they remain at low technology readiness levels with limited funding support. For instance, a solar-to-hydrogen reactor project received under ₹5 lakh ($5882), underscoring the small scale of radical research.

While incremental work is concentrated upstream in production and conversion, and radical work appears in scattered pockets, the midstream aspects of storage, transport, and logistics remain India’s weakest link. This mirrors global trends with international assessments identifying midstream technologies as the least mature parts of the hydrogen value chain, requiring substantial R&D before large-scale deployment. The result is a research landscape where activity is clustered at the beginning and end of the value chain, but the infrastructure that connects them remains thin. The country is still developing basic capabilities in this area, and only a handful of projects address this gap, including CSIR-AMPRI’s ADHERE composite pressure vessels, IIT Ropar’s ceramic membranes for hydrogen purification, and IIT Bombay’s compressed hydrogen–fuel cell integration system. Geological surveys in Rajasthan have identified salt-cavern potential for large-scale storage, but structured pilots have yet to start.

Choosing a Direction

This brings us to a central question: What is India optimising for?

The current portfolio suggests competing objectives, each with its own implications. If the priority is cost reduction and affordability, as the dominance of incremental research implies, then R&D should be followed by large-scale deployment, localisation of components, and strong industrial pull. However, this approach is unlikely to create distinctive intellectual property or position India as a leader in research and innovation.

On the other hand, if the goal is technology leadership, which is consistent with the NGHM’s stated ambition, then India requires far greater coordination, stronger pathways to scale up, and multi-year funding for breakthrough technologies. This would also involve longer development cycles, higher uncertainty, and support for moonshot ideas that may or may not succeed. Such attempts are necessary to build future capabilities and competitiveness in cutting-edge technologies.

At present, the portfolio reflects neither approach fully. Instead, small investments are spread thinly across almost the entire value chain. This breadth without depth makes it challenging to build leadership, whether through scale-driven cost competitiveness or through breakthrough innovation.

The challenge ahead is not merely one of ambition but also of alignment – aligning both laboratory innovation with industrial demand and public investment with long-term strategy. Since the hydrogen landscape is still developing, the strategic choices India makes now about where to direct R&D and how to scale it will shape its long-term position far more than in mature sectors. This will determine whether India can become a country that not only deploys hydrogen but also designs the technologies that define it.

We would like to thank Kunal Agnihotri for his help in designing the visuals featured in this piece.

Footnotes

- Our piece titled, ‘Beyond the Hype: Opportunities and Limits of India’s Green Hydrogen Pursuit‘, explores the feasibility of this

↩︎ - Electrolysis is a technique that uses electric current to drive an otherwise nonspontaneous chemical reaction. One form of electrolysis is the process that decomposes water into hydrogen and oxygen, taking place in an electrolyser and producing green hydrogen. ↩︎

- Proton Exchange or Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) electrolyser: A specific water electrolysis technology which operates under acidic conditions using a polymer to separate the electrodes. ↩︎

- Alkaline hydrogen refers to hydrogen produced via alkaline water electrolysis, a mature, cost-effective method using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen in an alkaline (basic) solution, offering a clean way to store renewable energy. ↩︎

- Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) use a hard, non-porous ceramic compound as the electrolyte. SOFCs operate at very high temperatures—as high as 1,000°C (1,830°F). High-temperature operation removes the need for a precious-metal catalyst, thereby reducing cost. It also allows SOFCs to reform fuels internally, which enables the use of a variety of fuels and reduces the cost associated with adding a reformer to the system. ↩︎