Research area: Adaptation and Resilience

Visualising the Heat Crisis: A Guide for Nonprofits

Hot Takes, Cold Action: How Heat is Misplaced Within India’s Bureaucracy

Extreme heat is no longer a distant threat. Over the past few years, it has claimed lives, destroyed crops, disrupted governance, and pushed India’s systems to the brink. In 2022, intense heatwaves devastated wheat crops, prompting an export ban. A year later, over 600 people suffered heatstroke at a state award ceremony in Khargar; 12 died. And in 2024, at least 33 people, including election officials, died from suspected heatstroke during the Lok Sabha elections.

This year is no exception. February 2025 was India’s hottest in 125 years, with many states breaching 40°C. Reports of heat-related deaths came in from Telangana, Gujarat, Punjab, and Odisha. Yet, despite these rising impacts, extreme heat continues to be treated by the bureaucracy as a seasonal, static, and short-term risk. In reality, heat is complex, pervasive, and deeply unequal in how it impacts different communities and sectors.

As part of our recent study on the implementation of heat resilience measures in nine Indian cities, we spoke to 88 officials across disaster management, health, urban planning, and labour departments. We found a fragmented and often inadequate understanding of heat as a policy issue which directly shaped actions and responses.

This blog draws on those conversations. It unpacks why heat remains overlooked by many parts of the Indian state, and what it will take to shift that mindset.

Bureaucracy misunderstands the threat of heat

The way bureaucracy responds to heat as a policy issue is fundamentally shaped by its understanding of the threat. This understanding – or often – misunderstanding, is influenced by two key phenomena: the rapidly changing nature of extreme heat, and the diverse, pervasive ways it impacts the population.

India has historically been a hot climatic zone, making heat a familiar presence. However, the extreme heat we face today is unprecedented, escalating at a much faster pace with threatening increases in heatwave days, humid heat days, and warm nights. This rapidly evolving nature of heat is a far more serious policy challenge than it is currently understood to be. Given the alarming rate of change, it becomes crucial for the bureaucracy to internalise this dynamic threat and adapt its response mechanisms accordingly.

Heat also impacts every sector and individual differently. Its impacts differ based on factors like the nature of work, built environment, and physiological conditions of an individual. Impacts spread from the workplace, affecting productivity and wage loss, to homes and public spaces, often hitting vulnerable, invisible groups the hardest. Many of these second and third-order effects are difficult to see and often go overlooked.

This inadequate understanding of heat’s complex, pervasive, and evolving nature shapes how the Indian bureaucracy currently responds to it: as a static, seasonal, and contained risk. As a result, heat actions are skewed towards short term reactionary measures, rather than long-term solutions.

During our fieldwork, we observed this misperception in three significant ways: first, in how heat is contained within bureaucratic memory; second, in how heat actions are currently implemented at local levels; and third, in how the state understands and records the health impacts of heat.

1. Bureaucratic memory around heat is seasonal

Heatwaves are still not fully understood by our systems, both in form and intensity, rendering them largely invisible. Heat seasons are often seen to last specifically from April to July, without much room for recognising their severity and preparing for the threat beyond these months. One official summed up this approach by remarking, “Now heat is past and we need to move on,” explaining how heat was no longer seen as a threat, with their focus shifting to the next seasonal issue – the monsoons.

This seasonal outlook towards extreme heat also means that even the most severe episodes of heat get treated as isolated events, not as signals of a growing, structural threat. This is partially due to a lack of technical capacity to understand the changing nature of the threat, coupled with shortage of staff. For an already overburdened local bureaucrat, a sentiment echoed by one who said, “There is so much work in the existing things which we have to do, let alone doing anything separately on our own,” there’s almost no institutional room for heat to be addressed. The result is a governance cycle defined by reaction rather than preparedness, falling short of being able to build any form of long-term adaptive capacity.

2. Heat actions lack local ownership and heavily depend on top down guidelines.

Effective heat actions must be locally driven, given their hyperlocal impact. However, current heat governance is heavily influenced by rapid response guidelines from state and central departments. We found this in response to questions on agenda-setting, as one official remarked, “We are waiting for guidelines from above.”

This strong dependence on national or state directives, from ‘dos and don’ts’ and awareness materials to specific funding, severely limits local ownership in solving for heat. As another official expressed, “It’s simply not on the agenda. If the central government issues directives or even encourages public awareness, then something will happen.“

These rapid response guidelines, while immediate, are filling a gap for a quick fix and a short time. They tend to be issued annually, acting as a temporary measure rather than fostering long-term, integrated solutions. However, their short term nature and a one-size fits all approach makes them an ineffective measure to build long-term adaptive capacity for heat, failing to protect the most vulnerable groups and address specific, evolving needs on the ground.

3. Invisibility of heat death reporting

The true human cost of heatwaves in India often remains obscured, primarily due to significant underreporting of heat-related deaths. While heatwaves are the deadliest natural hazard in Indian cities, official figures paint an incomplete picture. For instance, in 2024, India experienced a staggering 536 heatwave days (the cumulative total of heatwave days across all regions of India), the highest in 14 years, according to the India Meteorological Department. The official data reported only 41,789 suspected heatstroke cases and 143 heat-related deaths, a figure expected to be severely underreported.

This is partly due to the very nature of heat and how it presents during medical evaluations, from routine check-ups to emergency situations. Heat usually rides on – or hides behind – other medical conditions such as heart failure, respiratory distress, kidney dysfunction, or exacerbated pre-existing illnesses. This invisibility of heat as a ‘trigger’ often gets masked by the more immediate, observable physiological failures. It is, therefore, very hard to accurately attribute a death solely to heat, making it challenging for medical professionals to list it as the primary cause of death on certificates.

Despite the challenges in accurately attributing deaths, past experiences with high-mortality heatwave events have, paradoxically, played a crucial role in shaping future actions on the ground. As one official revealed, “Deaths this year have helped provide the services. This has helped create pressure. First time I have heard hospitals created heat wards.”

With low estimates of deaths in the official records, media coverage of heatwave deaths also often serves as a catalyst for bureaucratic action. Furthermore, an official highlighted the role of the media, explaining, “If anyone suffers from the heat, the media covers it extensively. Bureaucrats are keen to avoid negative publicity, so even if some of the actions seem superficial, they do get implemented effectively.” This underscores how the visibility of public health impacts, whether through media or, ideally, accurate official data, can push government bodies to address the issue.

How we see heat matters

The prevailing view of heat as a slow, silent threat has led to deep bureaucratic underestimation of its urgency. In our study, we found that heat actions in India are currently driven by short-term measures directly linked with how bureaucracy perceives heat, often missing out on major long term measures that could help build community resilience and enhance adaptive capacity. In cases where we found long-term actions being implemented, they were poorly targeted.

While national guidelines and central mandates have helped make heat visible as a public health issue within the bureaucracy, a comprehensive approach requires a fundamental shift in perception. This starts with building capacity both within institutions and the bureaucracy to assess, track, and respond to this evolving threat. It also means looking beyond traditional disaster management and integrating sectors such as labour and urban planning into heat discussions. Solutions must account for the ripple effects of heat: school closures, reduced work hours, infrastructure stress, agricultural losses, and more.

Finally, effective heat action needs to stem from the ground, locally owned by those directly affected by it. This necessitates targeted vulnerability mapping and active community involvement, as heat will impact those most who are already at the brink of survival. Dedicated funding channels, coupled with active community engagement and the involvement of stakeholders most impacted by heat in their daily lives, are crucial. This approach ensures that interventions go beyond temporary relief, tackling the fundamental sources of vulnerability, such as dangerous employment or living conditions, for lasting resilience. Only then can heat resilience become an embedded, continuous part of planning, policy, and decision-making.

Tamanna Dalal and Aditya Valiathan Pillai contributed to this article.

Heatwaves are coming. Can India handle it?

Why action on extreme heat in Indian cities is falling short

Is India Ready for a Warming World? How Heat Resilience Measures Are Being Implemented for 11% of India’s Urban Population in Some of Its Most At-Risk Cities

Executive Summary

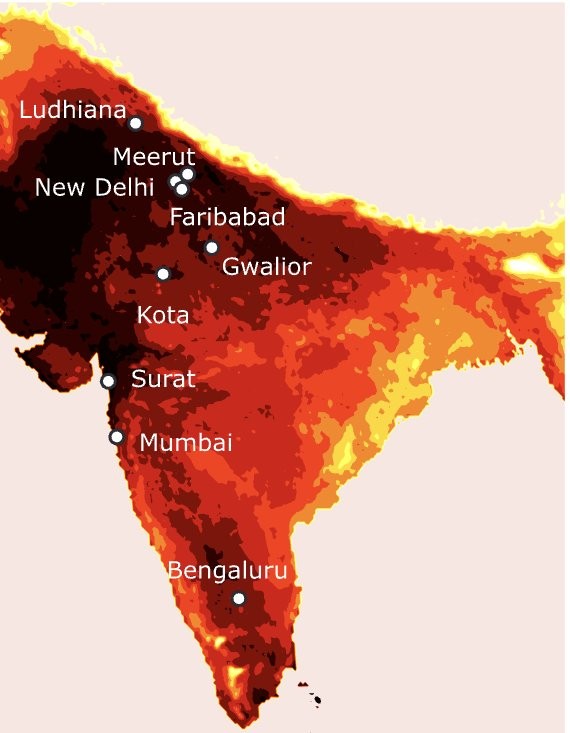

In this report, we study the implementation of policies and actions aimed at reducing extreme heat risks in nine Indian cities in nine states, covering a little over 11 percent of India’s urban population. We picked these cities based on how vulnerable they were to increases in extreme heat events as the planet warms. Using CMIP6 climate model output, we established which Indian cities with a population over 1 million (according to Census 2011) would experience some of the greatest increases in days with dangerous heat index values (a measure of the combined effect of temperature and humidity) compared to the historical average. Rapid shifts in the extreme heat index distribution induced by climate change may overwhelm communities’ adaptive capacity and lead to substantial increases in heat-attributable mortality and morbidity. This study is particularly urgent given recent indications that the climate may be warming faster than previously anticipated.

We conducted 88 interviews with city, district, and state government officials charged with implementing heat actions in these nine cities. Because heat adaptation requires a coordinated, cross-sectoral response, we conducted interviews with representatives of disaster management, health, city planning, and labour departments, as well as city and district administrators.

To assess how prepared these cities are for extreme heat in the coming decades, we catalogued short-term measures meant to save lives while paying special attention to heat solutions that are thought to bring long-term benefits. The latter include changes to urban form and the built environment – expanding urban tree cover, reducing density by increasing open space with building setbacks and parks, and changing design norms for heat-trapping buildings – and improvements in institutions that manage heat risk, from capacity-building efforts for government officials to the mandatory reporting of heat deaths to higher levels of government. Many of these actions take years to mature through refinement before they improve lives on the ground.

This is the first study to assess the implementation of extreme heat policies and actions across multiple cities in India.

This study is novel in its focus on long-term policies and their implementation challenges. We believe the issues and patterns highlighted in this report will be useful to cities, in India and elsewhere, that are attempting to complement their short-term responses with long-term heat risk mitigation through structural and institutional responses.

Key Findings

1. All cities report short-term emergency measures: These include actions like access to drinking water, changing work schedules, and boosting hospital capacity before or during a heat wave. If these measures are being implemented correctly, verification of which is beyond the scope of this study, this could be read as a positive story in achieving a minimum baseline of life-saving actions across cities in just over a decade since India’s first heat action plan (HAP) was published in 2013.

2. Guidelines and directives from higher levels of government drive short-term response measures, heat action plans (HAPs) seem to have a weaker effect on policy: Many of the life saving short-term actions reported across cities are a product of emergency directives from higher levels of government, including national and state disaster-management and health authorities, issued before or during a heat wave. HAPs, which often house long-term measures, seem to have a weaker effect on shaping heat actions because they are weakly institutionalised.

3. Many important long-term actions are entirely absent or poorly targeted: Actions like making household or occupational cooling available to the most heat-exposed, developing insurance cover for lost work, expanding fire management services for heat waves, and electricity grid retrofits to improve transmission reliability and distribution safety are missing from all cities. Expansion of local weather stations for more granular data on heat variation within a city, mapping urban heat islands, and training heat plan implementers were only seen in some cities. Other actions like expansion of urban shade and green cover, the creation of open spaces that dissipate heat, and the deployment of rooftop solar that could help with active cooling, among others, were implemented without adequate attention to populations and areas that experience the greatest heat risk.

4. Long-term actions are focused mostly on the health system: Long-term solutions were most commonly reported for the health system. These included actions like heat-specific training for health workers and creation of systems to monitor heat deaths. As a result, what emerges is a picture of very weak mainstreaming of long-term heat concerns in other crucially important sectors such as urban-planning departments. Health-system preparedness, while foundationally important to heat resilience, is meant to deal with the consequences of heat overwhelming the adaptive capacity of societies rather than prevent such situations from occurring.

5. Short-term actions are inexpensive, the shift towards long-term climate adaptation will require more finance: Over two-thirds of respondents reported adequate funding for heat actions and that they were drawing from a diverse range of existing sources spanning local, state and national funds. This is a consequence of a focus on short-term actions that are relatively inexpensive and temporary. Long-term structural changes, such as those mentioned above, will require dedicated resources.

6. Institutional constraints limit the possibilities for long-term action: The top problem identified by respondents was local coordination between government departments, both within and between municipal, district, and state government departments. More than half of all responses identified an inter-linked mix of personnel shortages, competing priorities, weak technical capacity, and insufficient acknowledgement of the heat problem as constraints.

Recommendations

1. Institutional Changes

(a) Strengthen HAPs in local governments: HAPs could help institutionalise long-term actions and monitor their effectiveness. They could also make crucial targeting mechanisms such as vulnerability assessments and the identification of urban heat islands mandatory.

(b) Draw on disaster mitigation funds that provide for heat wave preparation: As of late 2024, sub-national governments were allowed to draw on National and State Disaster Mitigation Funds to execute projects that mitigate heat wave risks. States should harness this line of finance to set up a pipeline of long-term risk reduction projects.

(c) Heat officers need appropriate institutional backing: Nascent conversations about creating Chief Heat Officer-type (CHO) positions should also consider how to equip them with adequate authority to solve the underlying institutional problems we have identified. In their absence, CHOs will probably face the same hurdles ‘nodal’ heat officers face today.

2. Capacity Building

(a) Create a targeted capacity-building programme for HAP implementation across India’s most heat-vulnerable cities: A sustained, multi-year capacity-building effort aimed at those in charge of executing departmental actions at the city/district level, in India’s ten most heat-vulnerable cities could rapidly improve India’s heat resilience prospects. We recommend starting with a small group with high potential impact and expanding over time to other cities.

(b) Establish trained disaster management support staff capacity at the district level: We recommend creating permanent and funded specialist positions in the most climate-vulnerable districts, with training for long-term risk mitigation.

3. Technology

(a) Create a highly-targeted active cooling programme: The rapid increase in temperatures and gap in long-term heat resilience strongly suggest that at-risk urban populations will turn to air conditioning to protect their lives and incomes. State and national governments should deploy a subsidy or large-scale purchase programme that allows these families to buy energy-efficient ACs. They must be targeted at portions of Indian cities with the highest heat risk, determined by the vulnerability assessment of its HAP.

(b) Use climate projections to expand the range of heat actions on the table: Only two out of 42 respondents asked had access to climate projections. Most implementers therefore did not know what the most dangerous days in a 1.5 degree world would look like in their cities. We recommend a national programme, anchored by national technical institutes, to make this information available to key state and city officials in the cities most vulnerable to rapid warming.

Now for a green Bharat abhiyaan

Extreme heat in India needs funds to fix

Unified action needed to tackle extreme heat and air pollution

Synergistic Impact of Air Pollution and Heat on Health and Economy in India

Abstract

In recent years, developing countries have been grappling with two significant environmental challenges—air pollution and increasing temperature. The impact of these issues on health and the economy has been extensively studied, leading to a growing body of literature highlighting their individual consequences. Understanding the synergistic effect of air pollution and increasing temperature on human well-being is a new topic of research that has received little attention in developing nations.

This chapter, published in the book The Climate-Health-Sustainability Nexus: Understanding the Interconnected Impact on Populations and the Environment (Springer), aims to address this gap in knowledge by thoroughly examining the existing literature to understand the combined influence of these environmental stressors and their implications for global health and the economy. We look into the trends of global exposure to air pollution and temperature and explore the pathophysiological pathways through which air pollution and increasing temperature affect human health. Our findings point to a severe lack of evidence on the synergistic impact of the two on human health in India. In the face of increasing climate vulnerability, the Indian economy is exposed to large degrees of risk through direct and indirect costs. It is crucial that the interplay between air pollution and heat be studied in depth. By dissecting these pathways, policymakers and healthcare professionals can develop more targeted strategies to mitigate the combined impacts of both on public health.

Finally, we focus on the health and economic co- benefits of implementing interventions to reduce air pollution and combat heat waves. By addressing these challenges in tandem, there is an opportunity to achieve greater overall benefits for both human well-being and economic prosperity. Through a deeper understanding of these interconnected challenges, we can strive for a healthier and more sustainable future for all, especially for those most vulnerable to poor environmental quality.